What’s Going On? How Jurors Arrive at Damages Awards

Susan G. Fillichio, Esq. and Steve Son, Ph.D.1

I. Introduction

The trend of jurors awarding unprecedented high damages awards, which began in 2018 and gained momentum in 2019, saw a brief hiatus during the second quarter of 2020. The minor blip in the trend was significantly impacted by the relatively low volume of cases being tried in that narrow window as a result of the pandemic (though certainly, other factors may have contributed to the reluctance of jurors to award damages in that timeframe). Once jury trials resumed, albeit sputtering in volume compared to pre-pandemic times, the damages trends leapfrogged right back to an overall upward climb.[2] Corporate defendants and defense counsel continue to be concerned, and even shocked, by the verdicts and continually ask us, “Why are the compensatory damages awards so large? Where did that number come from? How could the jury have found that the company acted with malice or reckless disregard under the circumstances? What is going on with jurors these days?” To provide some insight into how jurors make decisions about awarding damages in lawsuits, we review some of the cognitive processes that drive juror decisions about money damages. We likewise share results from the Fillichio & Hastings 2023 annual National Public Opinion Survey©, which reflects juror attitudes commonly important in talc litigation.[3] Finally, we explore what influences jurors in determining compensatory and punitive damages awards.

II. The Beautiful Mind: Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases, well studied by psychologists for decades, are deviations from What People’s perceptions of what they see or hear are completely different.[4] Every person’s mind has adapted through a lifetime of experience, resulting in cognitive biases that affect the juror’s beliefs and reasoning processes.[5] Similarly, all of us employ shortcuts (heuristics) to understand the massive information our brains receive so we can function efficiently in the world around us. Some psychologists have classified cognitive biases as errors in judgment, whereas others conclude that they are rational deviations from logical thought and just “good engineering by the mind.”[6] How a juror’s mind functions and has adapted over the course of a lifetime (long before entering the courtroom) is determinative of how the juror will make decisions in the case. There are numerous biases that impact juror decision-making, and although a few examples of cognitive bias are common parlance and well understood (e.g., the hindsight bias), a few others merit some discussion here, as the Fillichio & Hastings team regularly encounters them with jurors in talc litigation.[7]

A. Hindsight bias

The hindsight bias refers to the tendency to think that events that occurred in the past were inevitable and more foreseeable than they were at the time as a result of knowing the eventual outcome. For example, the hindsight bias is in play with jurors who believe that it was foreseeable to medical science that breathing tobacco into the lungs would cause lung cancer. In asbestos litigation, jurors are consistently led to believe that companies knew, or should have known, by the 1950s (or even in the 1930s) that exposure to asbestos (including minute quantities) causes harm to the body. This purported trail of knowledge then leads jurors to conclude that the companies did not respond appropriately when assessing the potential health risks of their products because jurors are judging behavior that occurred 70+ years ago by modern knowledge and standards (e.g., current OSHA standards), even when those standards have changed or were not in place at the time. Similarly, everything in the modern world has a warning label; consumers are inundated with warnings, for example, when food products may have been processed in a facility with nuts. The current ubiquity of warning labels leads most jurors to conclude that companies in asbestos litigation should have placed warning labels on their products just to be safe, even if there was only a slight possibility of danger. We also often see the bias at work when jurors insist that companies should have kept, over decades (and sometimes over a century), all, or at least most, documents that relate to the manufacture and distribution of every product bearing the company name in anticipation of litigation just like this. There are numerous examples of jurors impacted by hindsight bias in all genres of litigation.

B. Confirmation bias

Confirmation bias is the tendency to filter information by favoring or focusing only on information that supports a pre-existing belief or hypothesis.[8] Gone are the days in talc litigation where jurors have never heard of talc being linked in some way to cancer. Jurors are often fuzzy in their recollection of just where or when they have heard or read about this link, are not certain of the disease(s) that the talc has supposedly caused, and perhaps cannot cite the name of the plaintiff or defendant in the verdict they heard or read about. Still, it is the rare juror in any jurisdiction now who has not encountered at least something about the topic. Even prior to voir dire, jurors hear immediately from the court in the joint statement, or from the parties in a mini-opening, that the lawsuit involves a plaintiff (or multiple plaintiffs) who claims she developed cancer as a result of exposure to the defendant’s (or multiple defendants’) product(s). Thus, for those jurors who already have a belief or even a gut feeling that there must be something to all of the discussion about talc and cancer, throughout the trial they will look for, process, and remember information that supports that belief. Indeed, just being called to serve in such a case may be all it takes to trigger the confirmation bias. Further, jurors who enter the courtroom with predispositions about talc being harmful will rely upon and focus on information that supports these predispositions, such as case studies of only a couple of individuals who allegedly developed cancer from their use of talcum powder products (while ignoring the large sample epidemiological studies showing that repeated, massive exposure to talc does not cause or contribute to mesothelioma).

C. Availability bias

The availability heuristic is the tendency to overestimate the likelihood of an event occurring based on how readily the event comes to mind, which is often determined by how available it is in the public domain.[9] It is no coincidence that plaintiff lawyers in talc litigation have flooded the airwaves and social media with advertisements and slanted broadcasts about the purported dangers of talcum powder products. The lawyers pay for these advertisements and cable network broadcasts and misleadingly call them “documentaries,” even though there is no attempt to present thorough or balanced information on the topic. As a result, as noted above, it is the rare juror who has not encountered a discussion of the controversy of talc. This barrage of plaintiff-favoring information in the public domain, and a tactic used many times over the years in other contexts, seeks to capitalize on this heuristic that a juror hearing the same information over and over again is more likely to believe it is true.[10] Additionally, when jurors read or hear about large verdicts in these types of cases against companies with household names, they are more likely to stand out in jurors' minds. Thus, the information available in the public domain about these verdicts skews jurors’ perceptions of the dangers of using talc (as well as the amount of damages that are appropriate to award in these cases due to anchoring, which is addressed later in this article).

D. Conservatism bias

Conservatism bias is the tendency to place greater weight on one’s existing belief and give less weight to evidence that contradicts it, resulting in a reluctance to change one’s view in the face of otherwise persuasive information.[11] For example, when a juror has a predisposition that talc causes cancer, despite the juror being confronted with epidemiological studies with very large sample sizes showing a low incidence of disease in large numbers of highly exposed populations (e.g. the miners and millers studies), the conservatism bias may well be at play when the juror resists a change in the belief. This bias may also explain why jurors who are aware of the dangers of asbestos because of the need for abatement in schools and homes are slower to accept information pertaining to fiber types or dose-response.

E. G.I. Joe phenomena

This cognitive bias, coined in 2014 from the 1980s animated television series G.I. Joe, has been defined as the tendency to believe that knowing about cognitive bias is enough to overcome it.[12] Ironically, the series closed with a tagline, “Now you know. And knowing is half the battle.” [13] Fillichio & Hastings and counsel alike often have observed jurors in voir dire who tell us words to the effect of “everyone has bias.” In such scenarios, a juror will admit to having a bias (e.g., against corporations generally), yet insist that she can judge a case fairly because she is aware of that bias. Notably, knowledge of one’s bias does not always eliminate biased behavior: a conscious understanding of a bias does not necessarily overcome a deeply felt emotion that led to the bias in the first place.[14] It is beyond risky to take a juror at her word that she can set aside her bias and judge the evidence fairly for both sides because it is, in fact, a bias that cannot be set aside.[15]

III. Juror Attitudes in Talc Cases that Impact Verdicts and Damages

How do these biases manifest in jurors? What do we see during the voir dire process? In addition to conducting numerous jury research studies and supporting counsel in dozens of talc trials, Fillichio & Hastings has conducted annual nationwide surveys over the last three years focused on issues important in all types of litigation, including talc cases. We share below some of the pertinent data from our most recent survey in September 2023, wherein we queried 1,193 jury-eligible respondents across the country.

A. Science

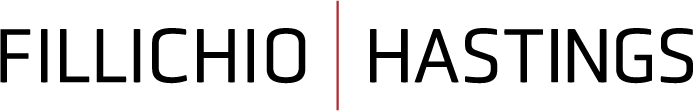

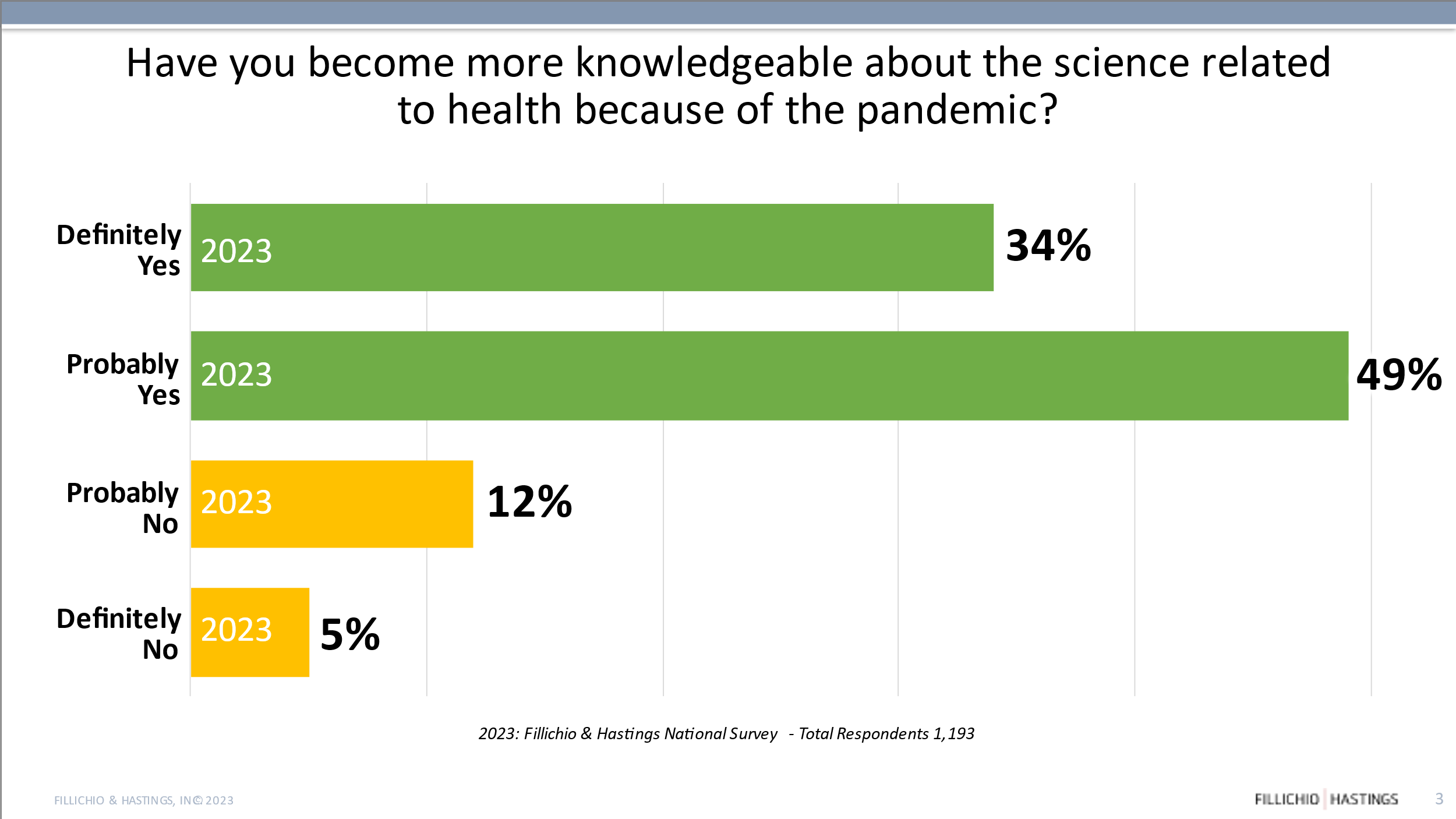

As a result of the pandemic, most respondents (83%) indicated becoming more knowledgeable about science related to health. Further, as a result of the pandemic, more than half of the respondents over the past three years indicated becoming more trusting of science and scientists.

B. Talc

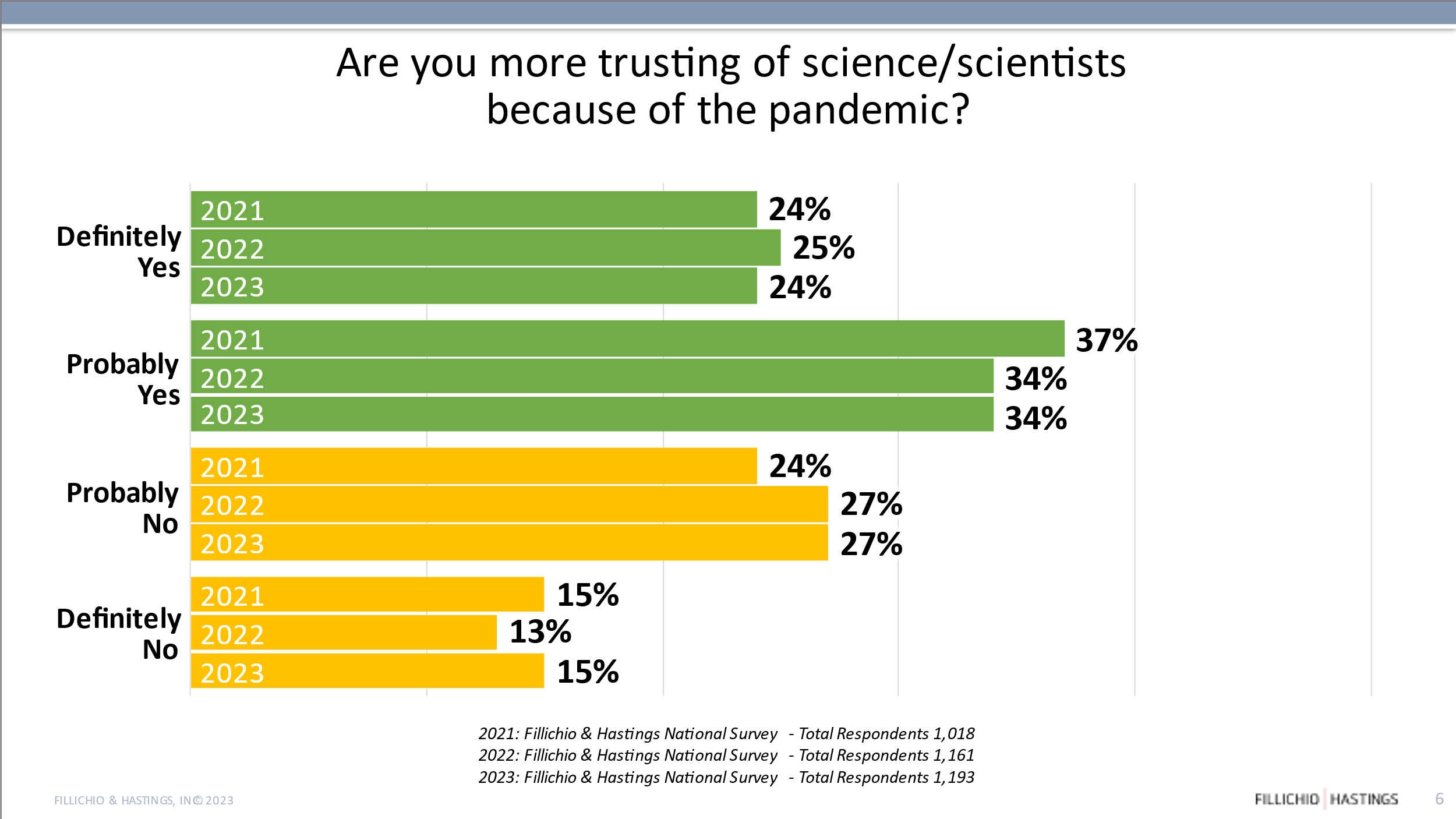

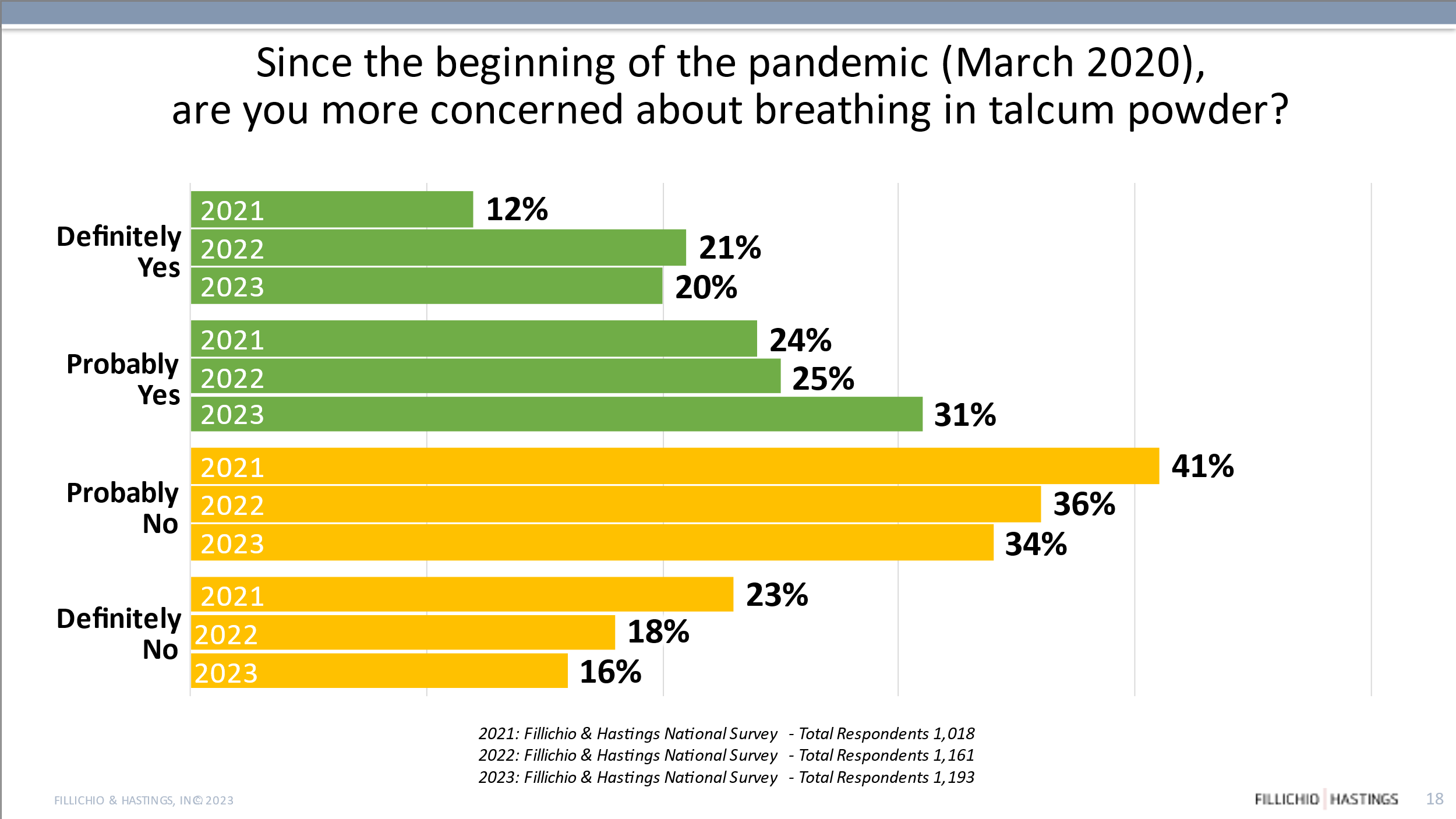

While the percentage of respondents who are concerned about what they breathe in, excluding Covid-19, has been steady over the past three years (61% of participants in 2021 and 62% of participants in 2022 and 2023), the number of respondents who are more concerned about breathing in talcum powder since the beginning of the pandemic has gradually increased (36% in 2021, 46% in 2022, and 51% in 2023).

C. Corporations

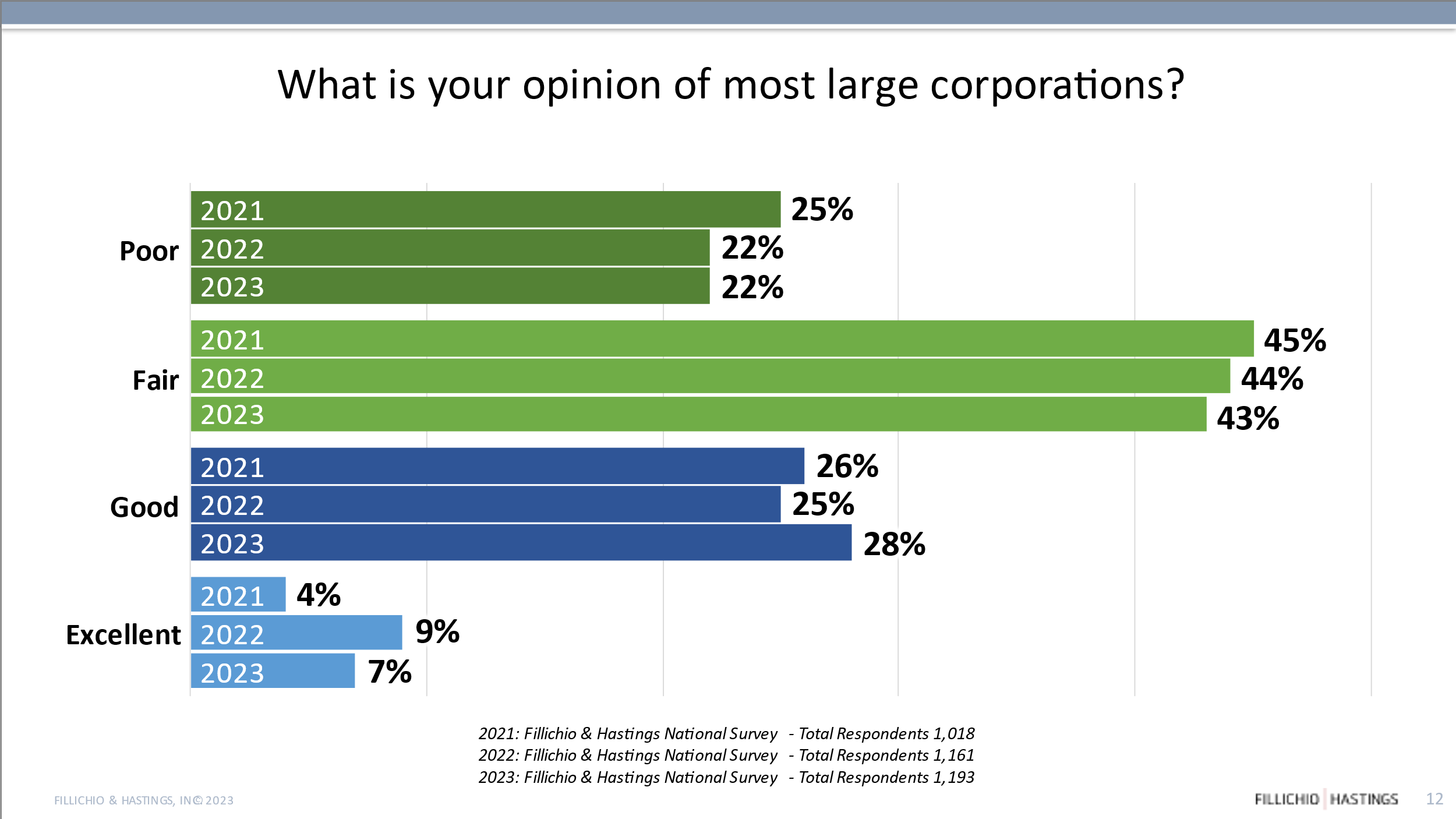

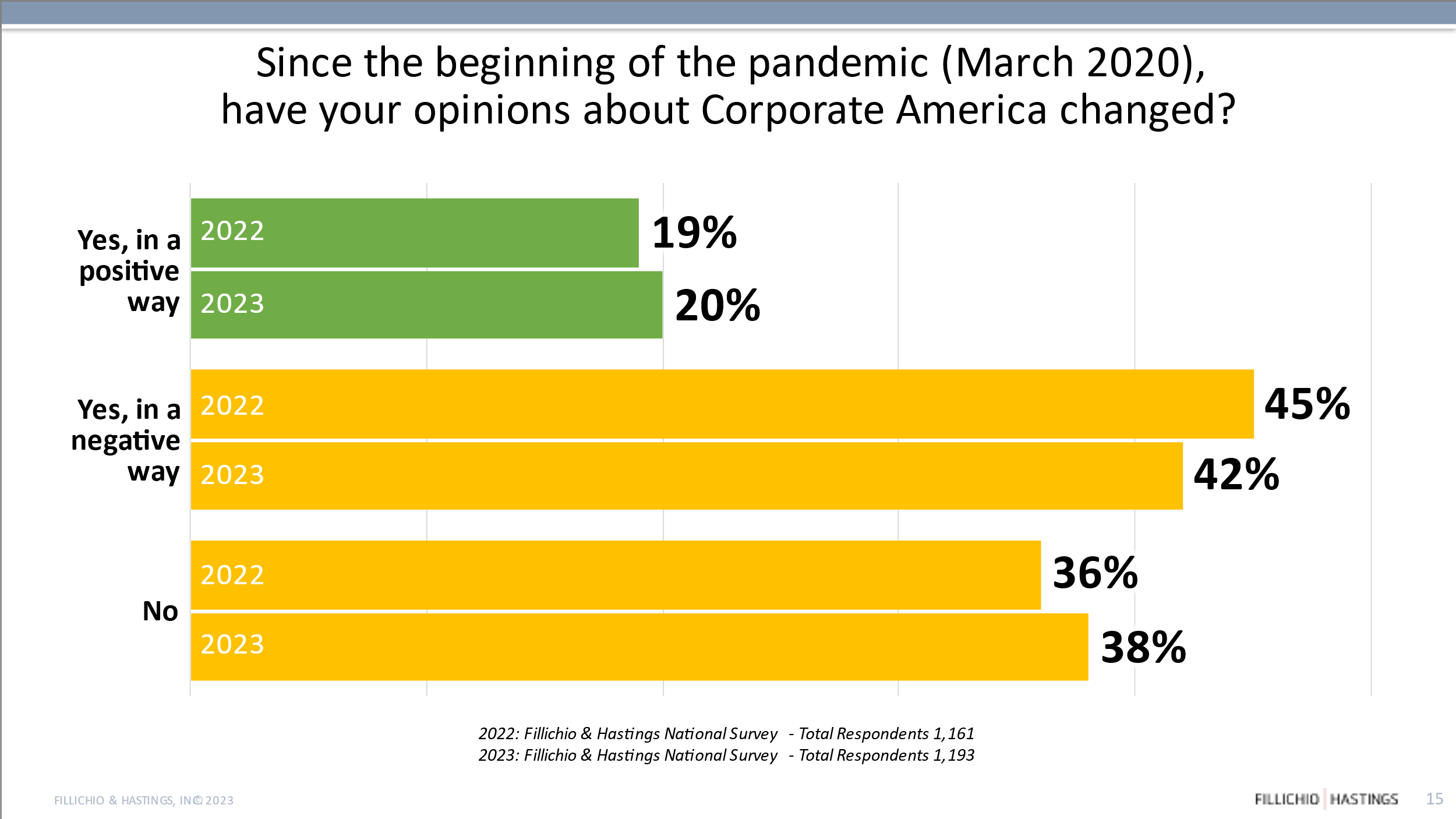

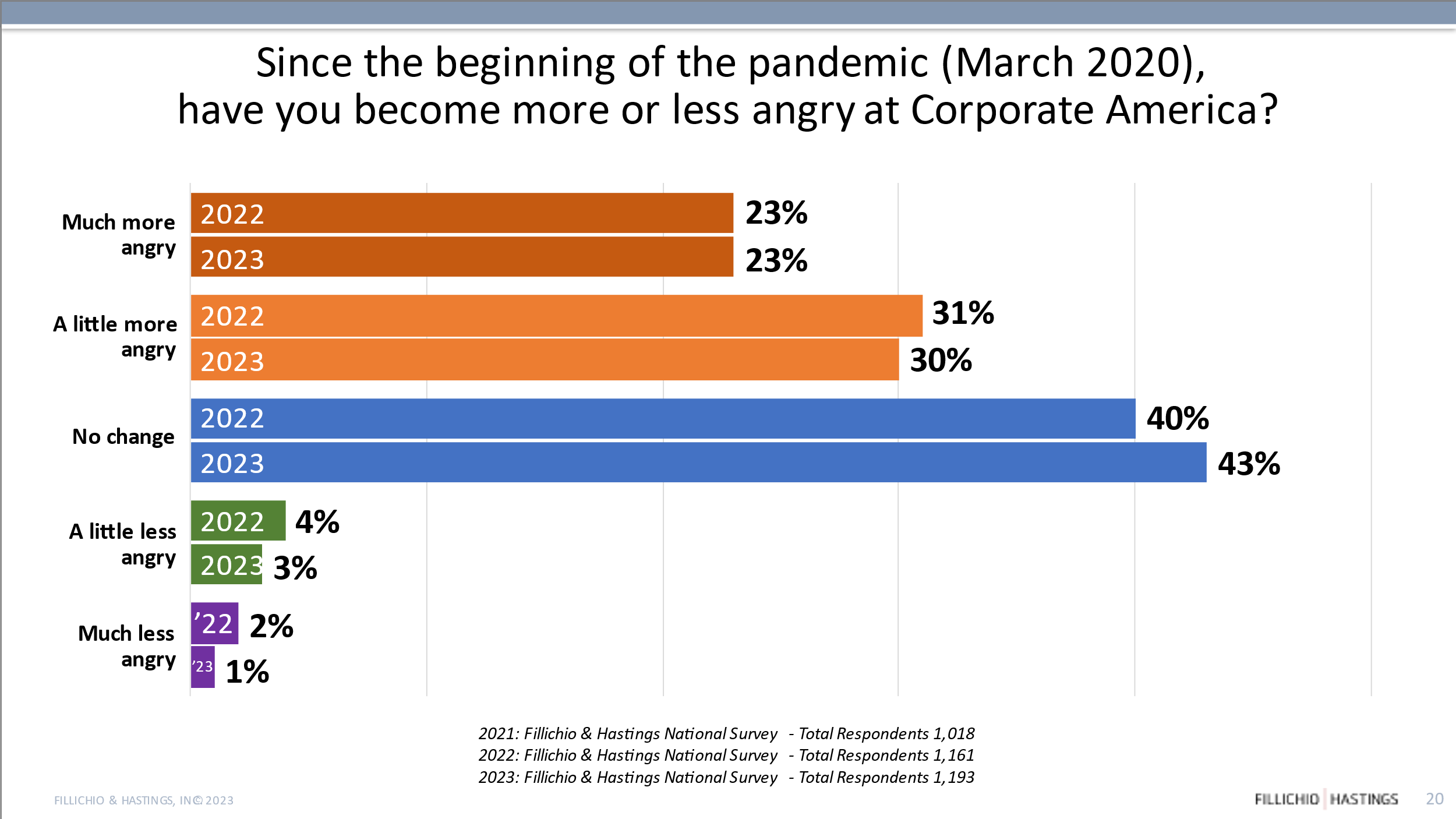

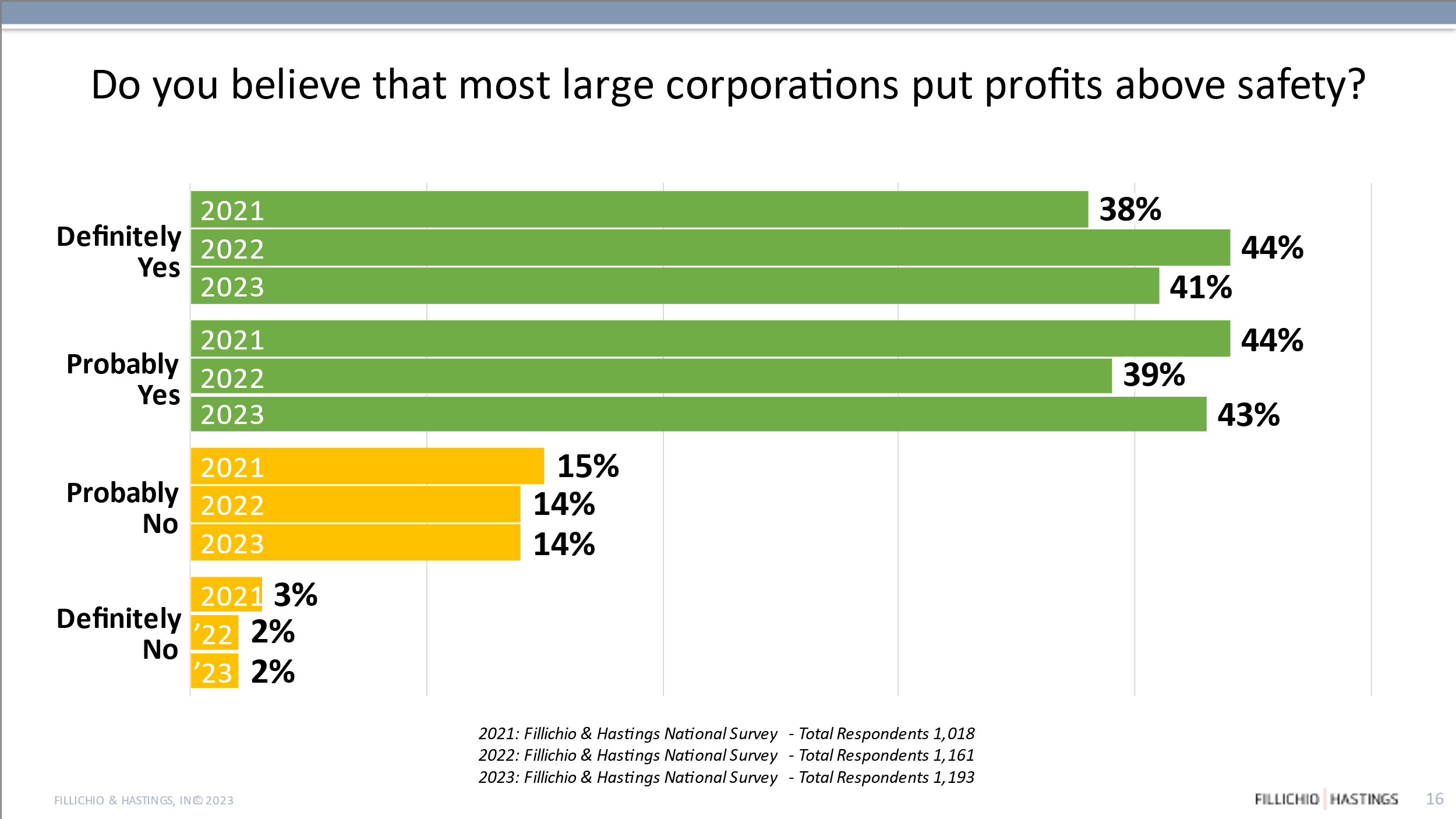

Across all three years of our survey, most respondents indicated having a fair or poor opinion of large corporations (65% most recently in 2023). In addition, since the beginning of the pandemic, many respondents reported that their opinions about Corporate America had changed in a negative way (42% most recently in 2023) and more than half of the respondents (53% most recently in 2023) became angrier at Corporate America. So, not only are many people’s opinions changing in a negative way, but pre-existing negative opinions are getting stronger. This negative bias towards corporations is further illustrated by the fact that most respondents across the three years believe that most large corporations put profits over safety (84% most recently in 2023).[16]

IV. Influences on Jurors in Determining Compensatory and Punitive Damages

With an understanding of both commonly encountered cognitive biases and pertinent juror attitudes in talc cases, we turn to the processes and issues that impact jurors in making decisions about damages. During voir dire, plaintiff lawyers in personal injury cases consistently inquire of jurors about their willingness to award millions of dollars in damages, or whether there is a maximum amount in their minds above which they will not go. Jurors’ responses to such inquiries often include questions about whether or not they will receive jury instructions or other guidance from the court about how to arrive at those damages awards. The answer is “no” in these types of cases, as there are no formulas and the jury instructions on the topic of damages are often confounding to jurors.[17] Most jurors relate that they feel completely unqualified to make such determinations. Likewise, even in mock trial studies (which are shorter and more linear in nature than any actual talc trial), surrogate jurors consistently puzzle over how to arrive at their awards. In the absence of a “how-to” guide, and because there is no supervision over the process of deliberations, what factors do jurors consider and how do they arrive at their awards?

A. Severity of the injury

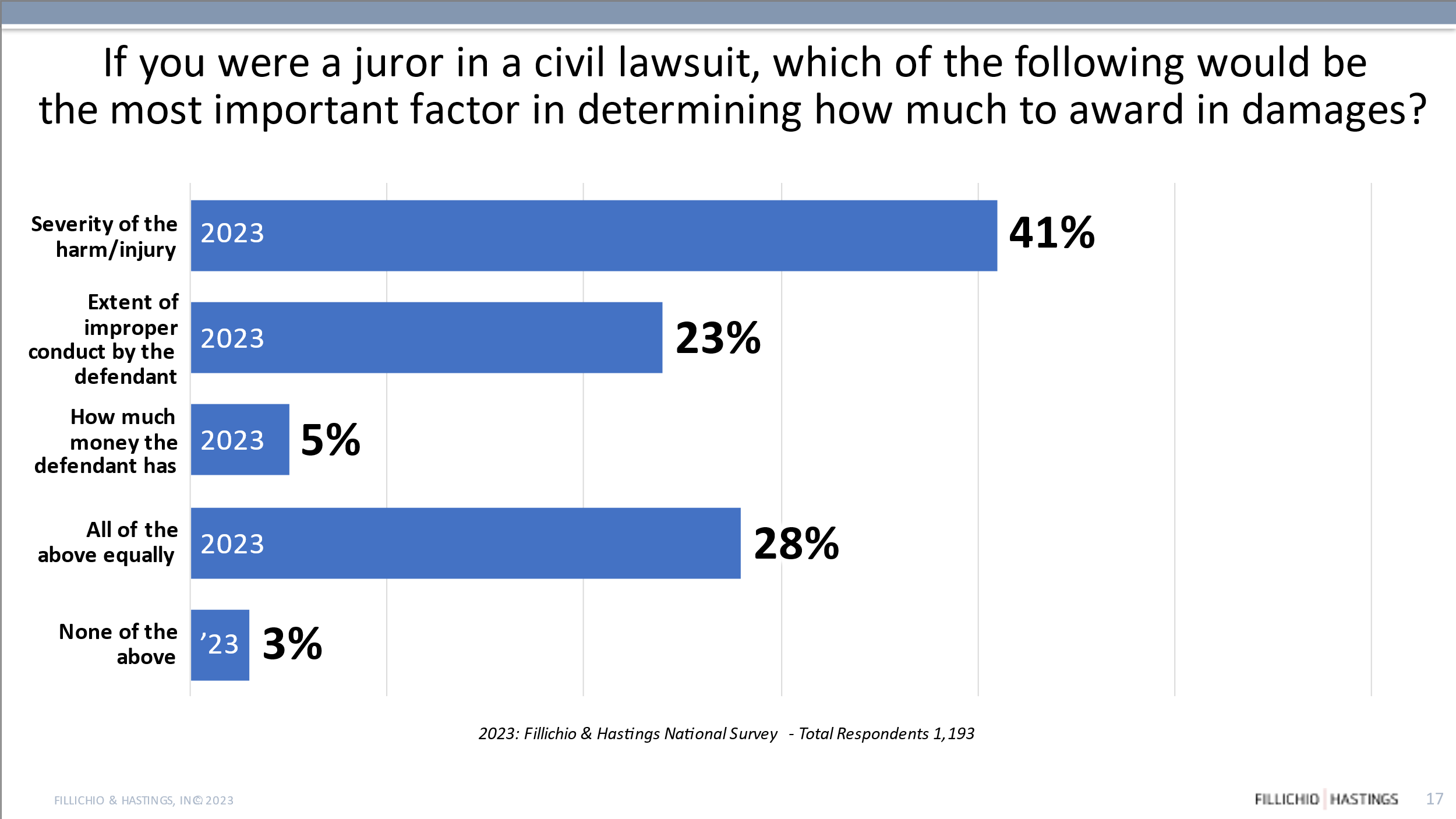

In 2003, psychologists Edith Greene, Ph.D. and Brian Bornstein, Ph.D., synthesized the existing research on the cognitive processes employed by jurors in determining damages in personal injury lawsuits. They concluded that the most important factor for jurors in determining compensatory damages is injury severity.[18] The Greene and Bornstein model, even though published two decades ago, remains applicable today, as confirmed repeatedly in our post-trial interviews with jurors. Notably, at least 41% of the respondents identified injury severity as the most important factor in determining how much to award in damages.

While every jury deliberation proceeds differently, what remains consistent is that as severity of injury increases, so do compensatory damages awards. For example, cases involving plaintiffs suffering from quadriplegia, a significant brain injury, or cancer result in verdicts that are higher than those wherein the plaintiff has sustained less severe injuries (even injuries such as burns or spinal injuries from a car crash).[19] Evidence that impacts juror perceptions of severity of the injury includes: indicators of physical harm, injury, or pain to the plaintiff; invasiveness of required medical treatment; the presence at trial (including by video deposition or live stream) of a dying or deceased plaintiff and/or family members who tell the story of the plaintiff’s life; the extent of mental or emotional suffering by the plaintiff; the impact of the plaintiff's illness or injury on the family's everyday life (e.g., the necessity of the family providing care to the injured or ill plaintiff, the impact on work life, children being deprived of experiences with a parent, etc.) and evidence of economic damages such as medical bills, annual wages, and vocational rehabilitation projections. All of these factors can play upon juror emotions, evoke sympathy, and trigger various biases.

Although it seems obvious that the loss of life is as severe as it gets, it is not just lore that damages awards for cases wherein the plaintiff, or the plaintiff’s loved one, has died are most often lower than those in which the plaintiff survives. Both the published literature and Fillichio & Hastings’s experience (with a few rare exceptions) confirm that a surviving plaintiff will be awarded more in damages than a deceased plaintiff. Thus, a plaintiff suffering from brain damage or quadriplegia is likely to be awarded more compensatory damages than the estate of a deceased plaintiff. Hence, there is no surprise by the rush of plaintiff lawyers seeking “preference” in trial assignment dates for terminally ill or injured plaintiffs.

Importantly, both the published literature and our experience reflect that severity of injury also impacts juror decision-making on the issue of punitive damages.[20] Although most jury instructions are straightforward about the purpose of punitive damages, the instructions also confirm that there is no formula for determining them. Thus, jurors naturally gravitate back to a discussion of the evidence that is most important to them in determining compensatory damages - severity of the injury.

B. The conduct of the parties and the cause of the injury

Jurors routinely consider the defendant’s conduct in awarding compensatory damages, a factor which, in our experience in talc cases, is becoming as important to jurors as severity of the injury. Notwithstanding that the defined purpose of compensatory damages is to make the plaintiff whole, and even in the face of a specific instruction advising jurors that they are to fairly compensate the plaintiff with their verdict (not punish the defendant), jurors at trial and surrogate jurors in mock trials consistently discuss the defendant’s conduct in determining compensatory damages awards. Jurors discuss whether or not the defendant’s conduct made the injury worse, and/or that the injury never would have occurred in the first place absent the defendant’s conduct. Generally, a defendant that actively commits harm is more blameworthy than a defendant that has failed to act; not surprisingly, the former scenario results in higher compensatory damages.[21] In talc litigation, the current strategy by plaintiff lawyers is to build the entire case around the defendant’s conduct. Defendants are typically accused of both committing acts that cause harm and failing to act. Plaintiff lawyers have greatly simplified the story of corporate conduct so that jurors can easily access and repeat it in deliberations. Consequently, even in trials where punitive damages are bifurcated, we have confirmed through post-trial interviews and extensive empirical study in these cases that jury deliberations in the compensatory damage phase center around the defendant’s conduct.[22]

In determining compensatory damages, jurors are also willing to discuss the plaintiff’s conduct as it relates to causing the injury, such as in automobile accident cases where jurors are prompted to determine comparative negligence. Similarly, jurors in product liability cases will assess the credibility of the evidence regarding the plaintiff’s purchase and use of a product. However, it is contrary to our experience in thousands of these cases to suggest that the plaintiff’s conduct is a primary focus for jurors in determining compensatory damages, despite targeted efforts by highly skilled defense counsel. In some cases, the strategy itself provides another example of the defendant’s conduct (blaming the victim) that deserves punishment. We have also observed reluctance amongst some jurors to attribute a high degree of fault to a severely injured plaintiff, even with a “but for” analysis of the plaintiff’s own conduct negating the injury altogether.

Of course, jurors are directed to consider the actions of the defendant when awarding punitive damages. In cases where the severity of the injury is more significant, and jurors determine that the conduct by the defendant has indeed contributed to the severity of the injury, jurors are inclined to award even higher punitive damages. Importantly, however, even in cases where injury severity is assessed as low, the actions of the defendant may still result in higher punitive damages awards if jurors determine that the conduct by the defendant caused or contributed to physical harm, or if the defendant disregarded the health or safety of the plaintiff (or others). Relatedly, the defendant’s conduct even during the course of trial can be a significant focus of jurors in determining punitive damages awards. As noted above, juror perceptions that defendants are blaming the plaintiff, misleading them about the defendant’s financial condition, or “fighting” the liability finding by the same jury in a bifurcated trial, have also contributed to higher punitive damages awards. In fact, compensatory and punitive awards are highest when jurors conclude that the defendant’s conduct is so reprehensible that it is a threat not just to the plaintiff but to the entire community (invoking the so-called reptile theory), coupled with juror perceptions that the defendant has significant profits and a healthy financial condition.[23]

C. Making the plaintiff whole

After jurors have determined liability (or at least the majority have agreed to this finding), they seek to make sure the plaintiff gets what she deserves through the process. Indeed, they are often instructed to do so in jury instructions. Even most defense-oriented and more conservative jurors, who may have voted against the liability verdict, eventually support the notion of making the plaintiff whole. Jurors generally reflect on their own experience and what such a loss would mean to them. Strong plaintiff jurors often become advocates, reinforcing the momentum in favor of the plaintiff by again reviewing the severity of the injury and conduct of the defendant to arrive at what it will take to compensate the plaintiff for the loss. Counsel may expect that jurors will determine compensatory damages by using a mathematical formula, such as the plaintiff has experienced “x” number of days of illness or injury or has “y” number of years left in her life, which equates to “z” dollars. However, research shows that jurors are looking for the “gist” of the damages to make the plaintiff whole.[24] Where the conduct of the defendant is deemed to have caused harm beyond the plaintiff, jurors often consider ways to make the community whole in addition to awarding monetary damages (most of which are unavailable through the civil justice system, such as injunctive relief).

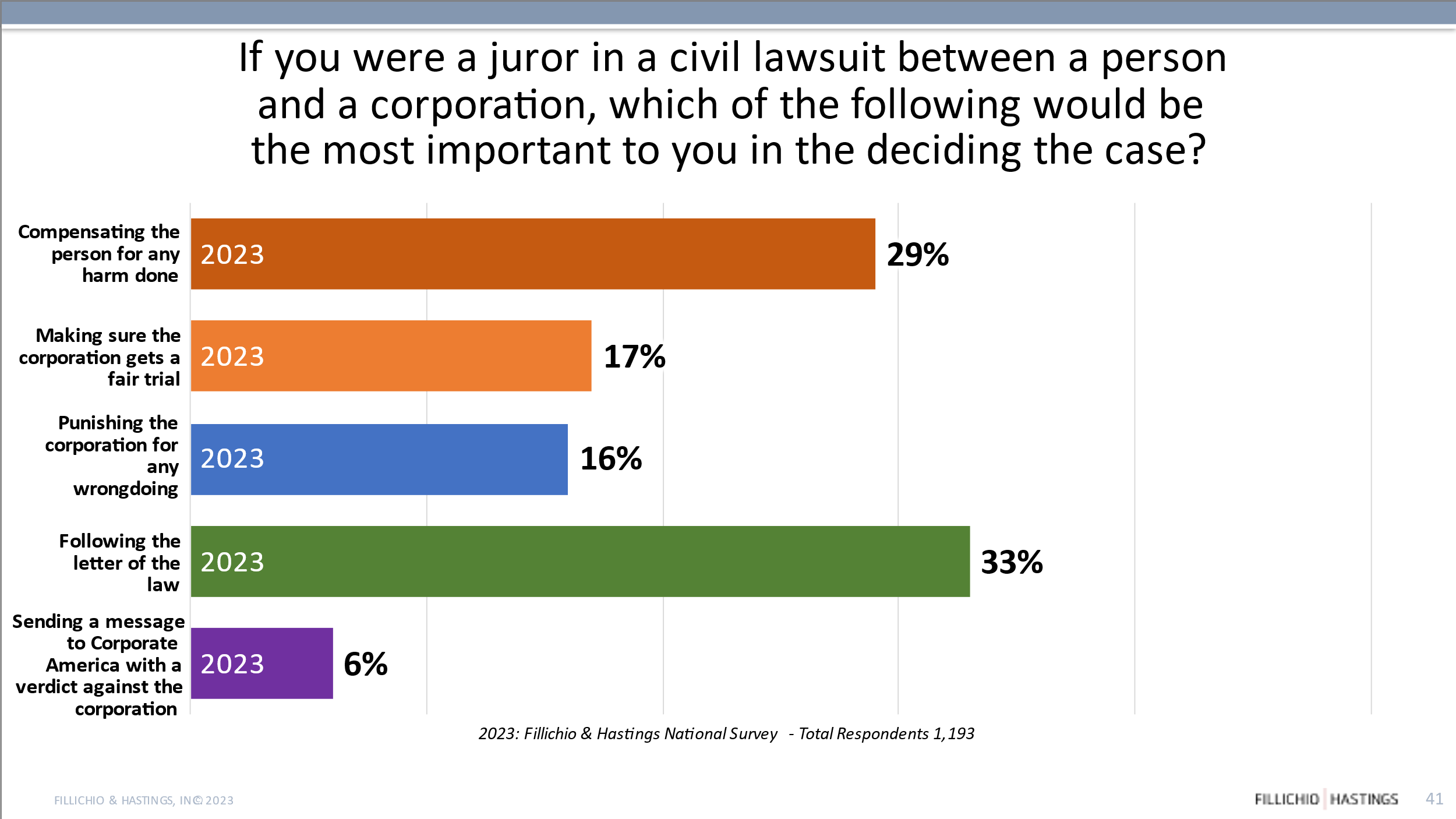

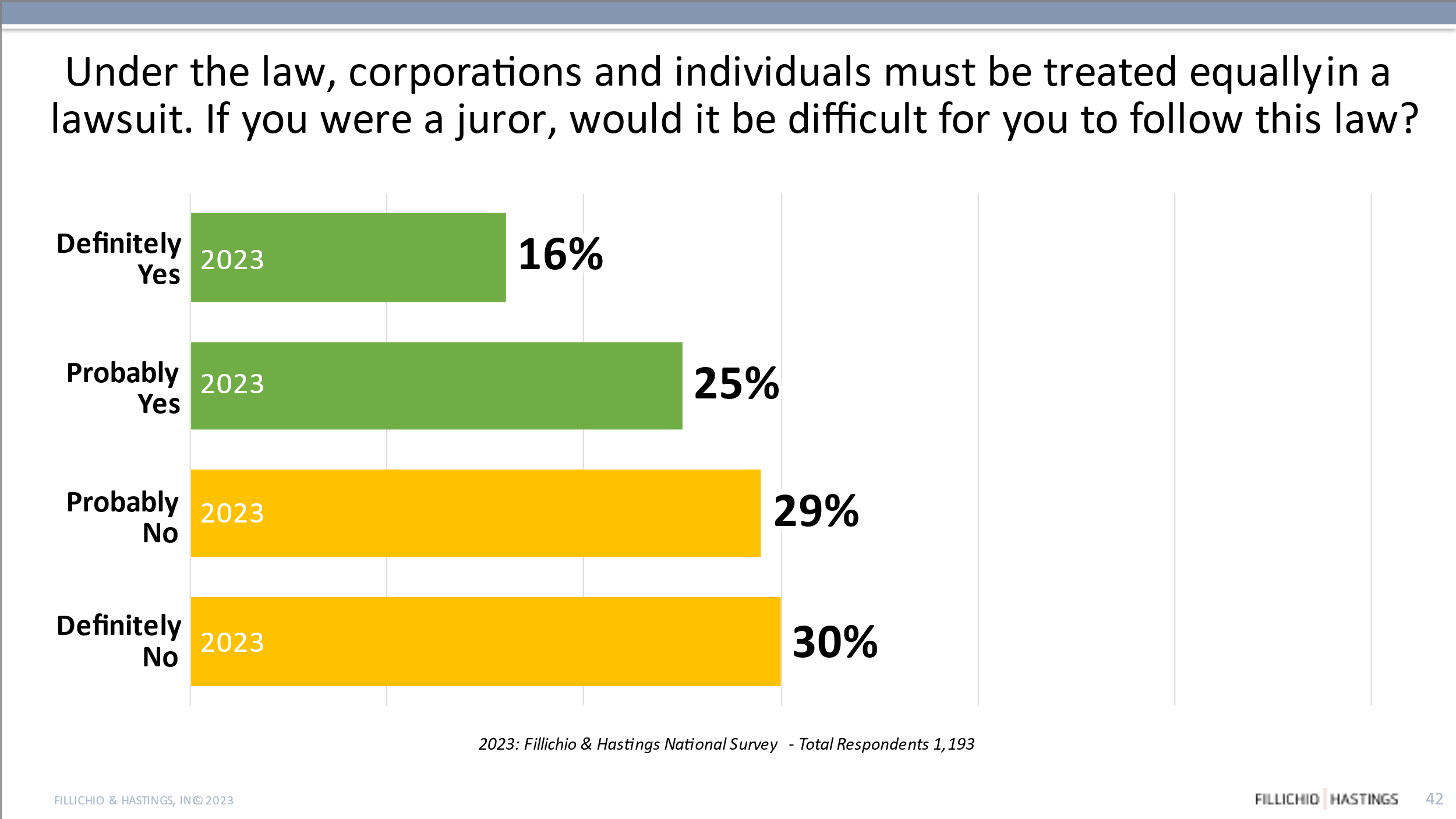

Conversely, jurors are generally much less interested in ensuring that the corporation gets what it deserves through the trial process. As confirmed in our national survey, while some of the jury-eligible respondents attest to the importance of following the letter of the law (33%), and many often confirm that they can follow the law and treat companies the same as individuals at trial (59%), a far lower percentage identifies ensuring that the corporation gets a fair trial as most important in deciding a case (17%).

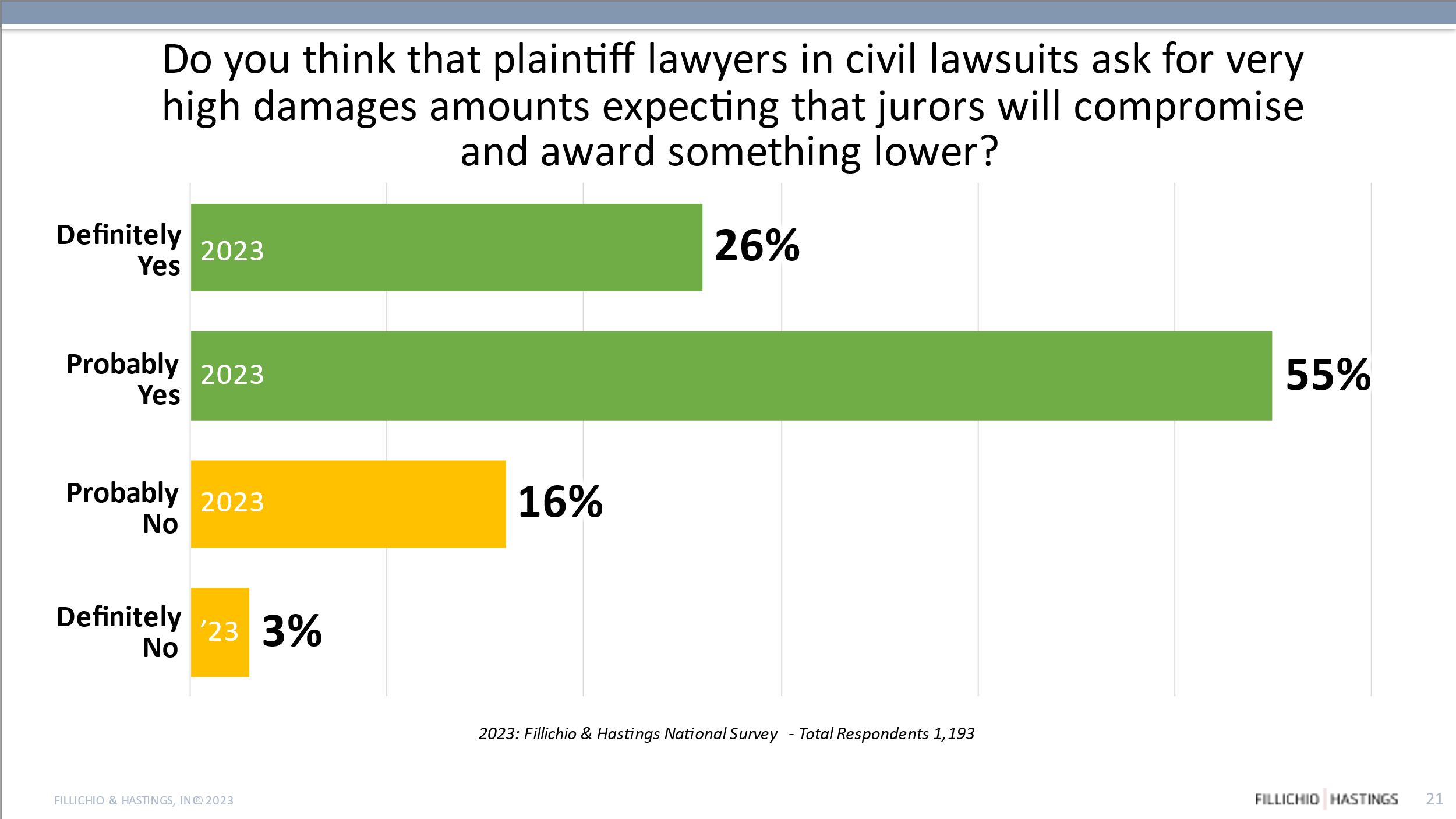

D. Anchoring

Anchoring is the tendency to unduly rely on the first piece of information received on a topic. Thus, when jurors hear plaintiff lawyers asking for “millions of dollars in damages” early in voir dire, the anchoring bias is already triggered. Jurors, of course, debate the topic of damages, and adjustments in the process are typical; however, jurors adjust off the original anchor and the final amount is biased toward the original anchor.[25] Most jurors are aware that plaintiff lawyers inflate their demands, hoping for jurors to compromise at a number closer to the middle (with the defense number serving as the lower anchor). This was confirmed by the respondents in our most recent annual survey in which 81% indicated that they believe plaintiff lawyers ask for very high damages expecting jurors to compromise and award something lower.

Even though jury-eligible individuals are aware of these attempts by plaintiff lawyers to inflate damages awards (both compensatory and punitive awards), our experience shows that starting with a very high anchor remains an effective tactic to increase damages. Because of the influence of an anchor, plaintiff lawyers know that the higher they go with their demand (within reason),[26] the higher that middle ground becomes.

The decision for the defense on whether or not to present a counter anchor other than zero can be tricky, as some jurors consider any damages number suggested by the defense as an admission of liability. However, on the other hand, we have often heard jurors remark that they focused only on the plaintiff anchor in their deliberations because there was no other number to reference. When counter anchors are presented by the defense, defense-minded jurors at least have an additional tool with which to counter plaintiff juror arguments on the discussion of damages and are useful tools in certain cases.

Where punitive damages are at issue, anchors are typically provided through company financial records. Perceptions that companies are minimizing or obfuscating the information on financial records provide jurors with additional affirmation of their determination of malice, recklessness, or fraud in the first instance, thus resulting in even higher punitive damages awards. The anchors here are likewise influenced by the availability heuristic and amounts jurors perceive to be enough to send a message to the defendant to prevent similar conduct in the future.

Of course, even in the absence of anchors presented by the parties, jurors provide their own anchors. Jurors have many easily accessible references from which to draw comparisons for the purpose of determining how much it will take to make the plaintiff whole. For example, when jurors are asked in voir dire about whether their lives have been affected by cancer, nearly all the hands in the courtroom go up. Given such widespread common experience, counsel can anticipate that deliberations include discussions of the staggering costs of medical care, hospital visits, surgeries, health insurance, etc., needed to make the plaintiff and their family members whole.[27] Consider further that rising food and gas prices, interest rates and inflation, lower rates of return on investments, college tuition which has more than doubled over the last 20 years, and soaring median home prices (when adjusted for inflation, up 40 percent over the past 20 years) lead to feelings amongst jurors that they need more money to be financially secure.[28] It is thus not a stretch for jurors to conclude that the plaintiff also needs more money now, and will need more in the future, to be made whole.

Widespread and highly publicized media and social media reports (an example of the availability heuristic at work) provide anchors on vast amounts of money that companies pay out or receive (even when not the defendant at trial), such as multi-billion-dollar corporate profits, executive compensation packages, massive salaries and bonuses paid to athletes and coaches, and funds spent on construction of new facilities. Finally, widely reported multi-million and even billion-dollar verdicts, especially in similar cases, also serve as a reference for what juries have awarded in damages in the past (and to some jurors, what should be matched or surpassed with their verdict). The frequent reporting of these exorbitant verdicts underscores the message that corporate conduct is in need of reform, thus creating a vicious cycle of sky-high awards becoming the perceived norm.

Conclusion

So, what is going on with jurors today? We know that as decision-makers, they come to the courtroom with unique attitudes, perceptions, and biases that impact how they make decisions. Those individual biases significantly influence how each and every juror will view the evidence in the case. Counsel’s awareness of cognitive biases regularly observed in jurors, coupled with an understanding of juror opinions about key issues in talc cases such as those in our annual survey, provides important insight into how jurors may view the evidence in these cases. In determining both compensatory and punitive damages, jurors consider the severity of the injury, the conduct of the defendant, and monetary anchors presented both at trial and those readily available from their own experience. Importantly, we know that there is no single factor or plaintiff lawyer tactic that is to blame for high damages awards (such as the reptile theory). Thus, there is no single strategy that will counteract the possibility of a high damages award. However, a deeper understanding of the influences that impact juror damages awards will not only assist counsel in evaluating the overall risk of damages awards for any given case set for trial but also may help minimize the negative repercussions of those influences.[29]

[1] Susan G. Fillichio, Esq., is a trial consultant and founder of Fillichio & Hastings. Steve Son, Ph.D., is a senior consultant at Fillichio & Hastings. For over 20 years, both have consulted in state and federal venues across the country in all types of civil cases, through hundreds of empirically sound jury research studies and in trials. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Nicole Mills, M.A., and Jacqueline Kirshenbaum, Ph.D. and for all data and charting meticulously compiled by Layne Hastings and the Visual Communications team at Fillichio & Hastings, Inc. Biographies of Fillichio & Hastings consultants are found at www.fhtrial.com.

2 Nonetheless, despite the trend, many of our clients have enjoyed defense or low damages verdicts even in these times.

3 Fillichio & Hastings's National Public Opinion Survey© has been launched three times: September 2021 (n = 1,018), September 2022 (n = 1,161), and September 2023 (n = 1,193).

4 Hence the effectiveness of presenting the very same information in several different formats through trial to appeal to various types of jurors, including different types of summaries and representations.

5 Haselton, M.G., Nettle, D., & Andrews, P.W. (2005). The evolution of cognitive bias. The handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 724-746). John Wiley & Sons.

6 Gigerenzer, G. (2006). Bounded and rational. Contemporary debates in cognitive science (pp. 115-133). Malden Ma: Blackwell.; Haselton, M.G., Nettle, D., & Andrews, P.W. (2005). The evolution of cognitive bias. The handbook of evolutionary psychology (pp. 724-746). John Wiley & Sons.

7 Our discussion here is limited in application to jurors; however, we note that these same cognitive biases are often observed in judges and arbitrators.

8 Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175-220.

9 Kuran, T., & Sunstein, C.R. (1998). Availability cascades and risk regulation. Stanford Law Review, 51(4): 683–768.

10 Kuran, T., & Sunstein, C.R. (1998). Availability cascades and risk regulation. Stanford Law Review, 51(4): 683–768.

11 Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. Science, 185(4157) 1124-1131.

12 Kristal, A. S., & Santos, L. R. (2021). GI Joe phenomena: Understanding the limits of metacognitive awareness on debiasing (No. 21-084). Harvard Business School Working Paper.

13 Bacal, J. (Executive Producer). (1983-1986). G.I. Joe: A real American hero [TV series]. Marvel Productions; Sunbow Productions.

14 Kristal, A. S., & Santos, L. R. (2021). GI Joe phenomena: Understanding the limits of metacognitive awareness on debiasing (No. 21-084). Harvard Business School Working Paper.

15 Developing a cause challenge for such a juror is of course the strategy; communicating why an identified bias is sufficient basis for the court to grant the challenge is specific to every courtroom and beyond the scope of this article.

16 Notably, the relative size of a company does not necessarily impact these views because, with rare exception, most companies are regarded as having more resources and power than the plaintiff (and thus greater responsibility).

17 Jury instructions for compensatory economic and non-economic damages, pain and suffering, emotional distress, etc., vary widely between the states. Nearly all, however, result in confusion and consternation amongst at least some jurors at trials and surrogate jurors in mock trials.

18 Greene, E. & Bornstein, B.H. (2003). Determining damages: The psychology of jury awards. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association.

19 Greene, E. & Bornstein, B.H. (2003). Determining damages: The psychology of jury awards. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association.

20 Greene, E. & Bornstein, B.H. (2003). Determining damages: The psychology of jury awards. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association.

21 Greene, E. & Bornstein, B.H. (2003). Determining damages: The psychology of jury awards. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association; Greene, E., Johns, M., & Smith, A. (2001). The effects of defendant conduct on jury damage awards. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(2), 228-237.

22 Likewise, jurors in bifurcated trials often misunderstand the process and think they are supposed to award all categories of damages, including punitive damages, in the first phase. This phenomenon occurs despite the court typically instructing jurors prior to opening statements that there will be a second phase of trial relating to punitive damages and that jurors are not to reach a verdict designed to punish the defendant in the first phase.

23 Becker, B.C. (1996). The robin hood bias: A study of biased damage awards. Journal of Forensic Economics, 9(3), 249-259.

24 Hans, V. (2014) What’s It Worth? Jury Damage Awards as Community Judgments, Wm. &

Mary L. Rev. 55(3), 935-969.

25 Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases: Biases in judgments reveal some heuristics of thinking under uncertainty. Science. 185(4157) 1124-1131.

26 Marti, M.W., & Wissler R.L. (2000). Be careful what you ask for: The effect of anchors in personal injury damage awards. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 6(2), 91-103.

27 Note that at least some data reflect that damages awards of the past did not adequately compensate plaintiffs for their injuries. For example, Greene, E. & Bornstein, B.H. (2003). Determining damages: The psychology of jury awards. Washington D.C: American Psychological Association, the authors suggest that compensation for serious and severe injuries lagged behind what was needed to cover medical costs even back in the 1990s.

28 Foster, S. (2023, July 6). Survey: The average American feels they’d need over $200k a year to be financially comfortable. Bankrate. https://www.bankrate.com/personal-finance/financial-freedom-survey/.

29 The most accurate assessment of the cognitive processes by which jurors will make decisions about a specific case is obtained through empirically sound jury research.

About the Authors

Founder, Consultant

Director, Consultant